In discussions about the care crisis, we often refer to the proverbial village needed to raise and nurture children. Nowadays, this village is attributed with far more responsibilities than just that, likely because certain family structures have eroded. Care is, after all, an enormous task—one that can only be managed well within a community.

Caring for one another is perhaps the most fundamental task of human existence, regardless of whether people have children. We need a “village” to navigate the diverse challenges of life without immediately falling into dependence on a highly extractive economic system. Yet today, only very few live in structures that resemble such a village. As a result, care work is becoming increasingly individualized.

A Dimension of Its Own

Care work—more precisely: unpaid care work—has immense dimensions. Each year, 117 billion hours of unpaid care work are performed. Of these, 72 billion hours are carried out by women, which equals 62 percent. The time spent on care work far exceeds that of paid work, which totals about 60 billion hours per year. Roughly one-third of unpaid care work—40.3 billion hours—is spent on childcare and caring for relatives. Of that, women contribute 28.2 billion hours, and men only 12.1 billion.

Moreover, care work cannot simply be left undone—it’s not optional. Jo Lücke, author and founder of the League for Unpaid Work, writes in Surplus magazine: “The nonstop nature of care responsibilities puts many into a mode of pure functionality—leaving it is often not an option. Feeding the child less, caring less for grandpa, or just not emptying the catheter is simply out of the question.”

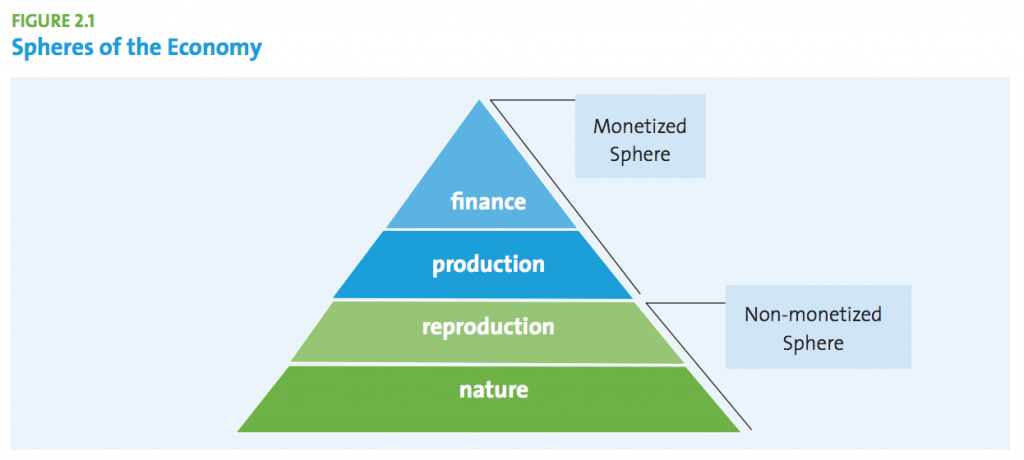

Externalized Care Work

To function as individuals and remain able to work, we need solutions. When the infrastructure of the proverbial village is missing, a phenomenon has emerged—particularly in the Global North: we must buy back all the things that were once mutually provided in village-like or familial structures. Care is increasingly being commodified.

Childcare, elder care, and household tasks are just three areas where often-precarious service industries have emerged—largely staffed by women. These industries fill the gaps in a system that desperately relies on care work but expects it without direct compensation.

Purchasing care services is, of course, a privilege. People with lower incomes often cannot afford childcare or domestic help. They depend on their own unpaid labor, which means women, in particular, have less time available for paid employment—thus reinforcing cycles of dependency. For single parents, this problem is even more pronounced.

Compatibility as a Simulation

The well-known consequence: women are increasingly pushed beyond their capacity by care burdens. As a result, they’re often unable to take on leadership positions in business and politics, where constant availability remains the norm. As long as organizations fail to recognize this, the idea of “work-life balance” remains a simulation. Part-time work or reduced travel becomes a dead end for women’s careers—when the current factors that actually advance careers are entirely different.

The higher women climb in organizational hierarchies, the more they are pressured to conform to existing norms. Given the unequal distribution of care work and prevailing double standards, women often have no choice but to decline leadership positions. Anyone interpreting this as a lack of ambition or a prioritization of “work-life balance” fundamentally misunderstands the issue. Pointing to outdated gender roles—which companies supposedly cannot influence—also misses the mark.

In an interview with Surplus, sociologist Melinda Cooper explains that we tend to focus on just two life models: “The neoliberal model of familial responsibility, in which the state transfers the costs of care work to the private family, or the Keynesian family wage system, in which the state indirectly subsidizes women’s care work via their husbands.”

Toward a New Understanding of Care

Companies would do well to take a comprehensive view of the conditions under which people perform paid work. Alongside care responsibilities, attention must also be paid to intersectional challenges. Neurodivergence, disability, socioeconomic background, and racism—as well as related experiences of marginalization and discrimination—all significantly impact a person’s ability to work. A modern, future-oriented company must acknowledge these factors; otherwise, it will continue to self-select against people with care responsibilities or other life challenges.

This is where decision-makers and leaders come into play. If their career paths have been largely free of care responsibilities, they have an obligation to recognize and close their perception gaps. Otherwise, it will be difficult—if not impossible—to create environments in which diversity can thrive.

This is about the crucial difference between representation and participation. Merely promoting women (or other underrepresented groups) into prominent roles is not enough. These individuals must be able to approach these roles without being forced to assimilate or risk burnout.

The problem: In both business and politics, the top decision-makers are usually “as far removed from active care responsibilities as one can be,” as Jo Lücke aptly puts it. How can someone design the conditions for compatibility when their own care experience is largely defined by outsourcing such tasks to others? This lack of lived experience undermines both credibility and outcomes.

What Companies Truly Need Now

A commitment to diversity and work-life balance is now part of the standard employer branding playbook. But without the structural conditions to support it, such promises remain empty. Truly diversity-sensitive organizations don’t ignore or stigmatize care work—they actively incorporate this reality into every decision.

What’s needed is not a single initiative, but a radical rethinking of all HR processes—from talent acquisition and leadership development to performance evaluation and goal setting. The question is no longer whether companies must engage with care responsibilities, but how and with what level of ambition they do so—without marginalizing or romanticizing care work.

A Radical Paradigm Shift

In many companies, linear career paths and so-called “performance continuity” are still seen as hallmarks of quality. Anyone who takes time off, scales down, or invests time in caregiving risks falling behind. Career is defined as a competition in availability—not as a reflection of competence, responsibility, or impact. These structures systematically exclude those who carry additional life responsibilities—be they parents, caregivers, or others.

Instead, companies should ask themselves:

-

What do careers look like that integrate care rather than rely on its absence?

-

How can leadership systems be designed for more than just full-time men in physical presence?

We need transparent promotion criteria, a reevaluation of part-time capabilities, flexible leadership tandems, and a culture where openness about care responsibilities is not an act of self-exposure, but a welcomed shared reality.

The handling of absences must change as well. Parental leave, caregiving time, or mental health crises should not be seen as interruptions but as evidence of lived reality and resilience. Those who take responsibility during these times develop skills that organizations also need: prioritization, crisis management, emotional intelligence. Why not finally recognize these as leadership qualities?

The Company as the Village

Ultimately, care is a team matter—not an individual challenge. And here, the circle returns to the “village.” Anyone offering flexible models must also equip leaders accordingly. It’s not enough for HR to promise work-life balance on paper while managers still penalize flexibility or maintain cultures of invisibility.

What’s needed in concrete terms:

-

Leadership training on care competence and biographical diversity

-

New HR metrics that make care responsibilities visible and help destigmatize them

-

A redesign of career paths and goal systems beyond permanent availability

-

Dialogue spaces where care biographies can be shared and validated

-

Integration of care into DEIB strategies—not as a side note, but as a core issue of participation

Because without recognizing care, every promise of diversity is hollow. If companies are serious about inclusion, they must change the conditions under which inclusion can thrive.

Care is not a private matter. It’s a test of the system. Those who want to build resilient, just, and future-ready organizations must see care not as a footnote in a CSR report, but as a structural dimension of the modern working world. What’s needed is courageous leadership—willing to question old performance ideals and embrace new forms of responsibility. Not because it’s “nice.” But because it’s necessary: for justice, for innovation, and for the future viability of our organizations.

(Photo credit: Drazen Nesic at Unsplash)

Text by Robert Franken, originally published here